By Guy Bryant

The first time I followed a diver into the entrance of an underwater cave with a camera in my hands, I knew I was chasing something more than just a picture. I wanted to share the experience and beauty of the underwater caves that I saw with other people that would never be able to see it. To do this, I wanted to capture the mood — the way the light fades to nothing just a few feet from the entrance, the way the rock walls are sculpted by underground rivers.

But back in 2008, I didn’t have the right tools for that vision. My first attempts were with point-and-shoot cameras inside underwater housings, relying on the built-in flashes. They were fine for snapshots, but in a cave, “fine” quickly turns into “frustrating.” The built-in flash was swallowed by the darkness almost instantly, leaving my subjects looking flat, lifeless, and surrounded by shadows that hid the beauty I knew was there.

The Gallery Section in the main tunnel of Devil’s Spring, Florida. © Guy Bryant

Sharper, Richer, More Alive

I realized I needed something more. Something serious. That’s when I decided to house my Canon 40D DSLR in an Ikelite underwater housing. I already had history with the brand — in the early 1970s, when I first started scuba diving, I’d used Ikelite lights to explore wrecks and reefs at night. I trusted their gear.

In 2009, I paired that housing with a single DS160 strobe. The change was immediate — the photos were sharper, richer, more alive. But they still weren’t the shots. The caves still felt too dark, the scenes too confined. So I doubled the lighting power, adding a second DS160. That helped… but I wasn’t there yet.

The main tunnel in Madison Blue Spring, Florida. © Guy Bryant

Creative Lighting Perspective

Then I had a thought: maybe the problem wasn’t just about how much light I had, but where it was coming from. A cave is a world of texture and depth, and light in the right place can make it come alive. If my dive model could carry a strobe, we could light the scene in ways that would never be possible with only camera-mounted flashes.

The idea was simple — if I was shooting from behind the model, they’d point their strobe forward to illuminate the cave ahead. If they swam toward me, they’d aim it behind to backlight the space they’d just passed through. That extra perspective could turn a flat image into something more revealing as in the hidden detail of the cave passages from scalloped walls to water carved formations.

The main tunnel in Telford Spring, Florida. © Guy Bryant

The Magic Setup

So I found a used DS125 for the model to carry. Suddenly, I had new creative possibilities. But underwater cave photography has a way of turning every solution into a new problem. The strobe sensors wouldn’t always trigger, especially if the model’s positioning wasn’t perfect. I experimented — moving the sensors, trying different angles. Eventually, I discovered the magic setup: mount the strobes to the back of the model’s tanks and place the sensor on their wrist or the side of their mask. From then on, the flashes fired almost flawlessly.

The Catacombs in Devil’s Spring, Florida. © Guy Bryant

Over time, my equipment grew. Now, my standard cave-diving photo setup is four strobes: two on my camera rig, two on the dive model. This gives me the ability to light not only the diver, but the space around them — revealing the grandeur of the passageway instead of letting it fade into black.

The Crossunder Tunnel in Madison Blue Spring, Florida. © Guy Bryant

Sharing Hidden Beauty

Cave diving is already an exercise in trust, skill, and precision. Add the challenge of photography, and it becomes a choreography of light and movement in a rarely seen underwater world. The visibility can change in seconds. The distance between me and the model can mean the difference between a perfect shot and nothing but shadows. But when everything clicks — the light, the angle, the water clarity — the scene is transformed.

These caves aren’t just black tunnels in the earth. They’re sinuous passages, carved by time, hidden from the surface world, and alive with a beauty that few people ever see. My camera, my lights, and my patient dive models allow me to share a little piece of that beauty. And every time I surface, I’m already thinking about the next dive, the next photograph, and the next chance to light up the darkness.

The Downstream Tunnel in Cow Springs, Florida. © Guy Bryant

Additional Viewing

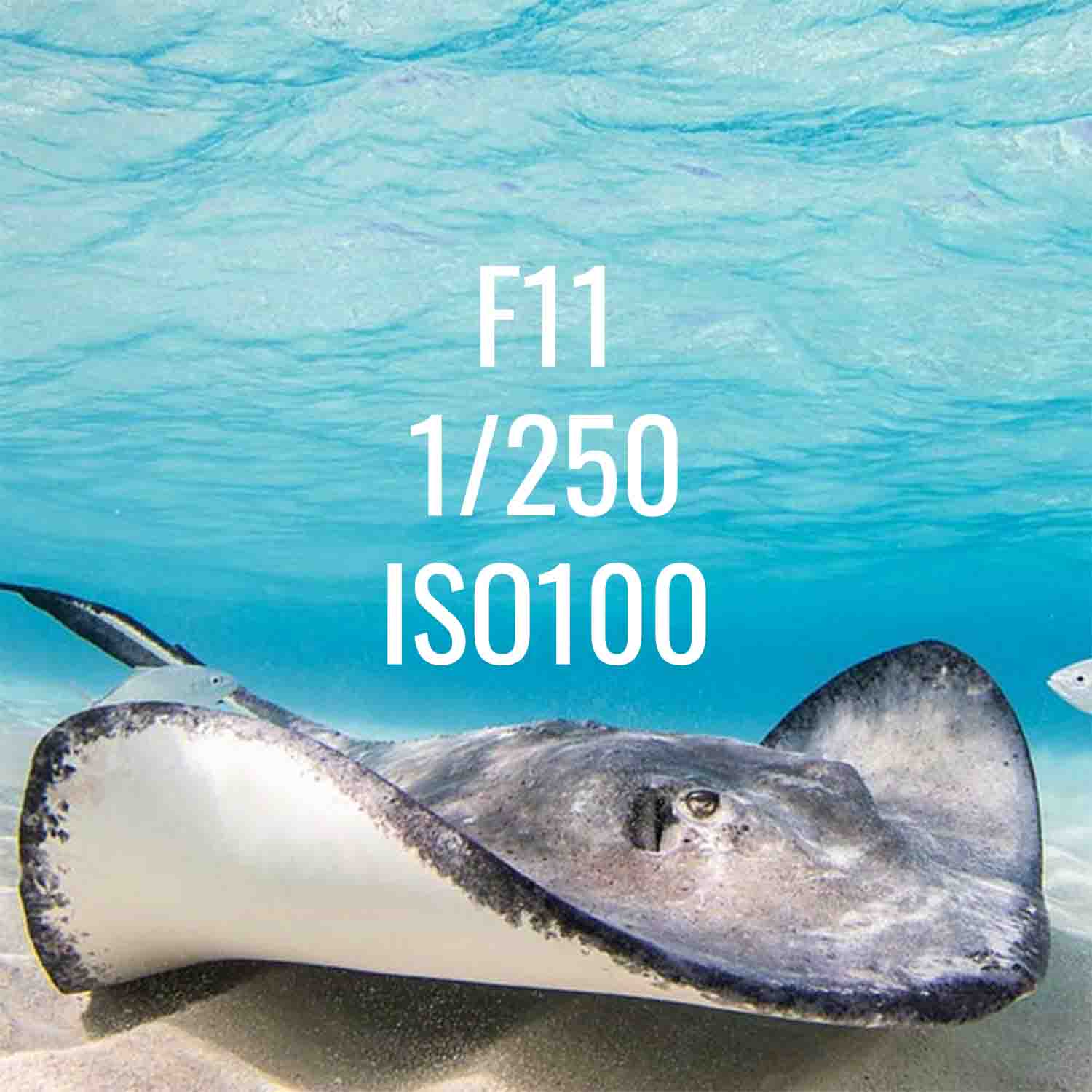

Caverns and Cenotes Underwater Camera Settings

Underwater Cave Photography with the Nikon Z7 II

Photographing Freshwater Cave Ecosystems 220 Feet Underground

Vintage Divers Underwater in the Florida Springs with the Canon R100

What Secrets Lurk Underwater in the Florida Springs at Night?

Guy Bryant is a legendary cave diver, underwater photographer, and lifelong explorer of caves, both dry and submerged. Since first taking up scuba diving in the early 1970s, he has developed a deep fascination with underwater caves and the technical challenges of capturing their beauty on camera. His images not only document these remote environments but also share their awe-inspiring beauty with those who may never see them in person. His book about his cave diving experiences, The Education of a Cave Diver, can be found on Amazon. His Coffee Table Book, Illuminated Springs – Volume 1, can be found on Lulu.com. Visit Guy's photography website at www.guybryant.com.