By Denise Pietsch

Barry remembers precisely the day he made a purchase that would change his life. It was 2004 and he was going to his local dive shop to buy his first Ikelite housing for the Nikon D100 and two DS-125 strobes. He was on his way to an island called Curaçao, with just 35 dives under his belt. He didn’t know where Curaçao was, let alone how to pronounce the name. But he knew enough to take a chance on a once in a lifetime adventure. Thus began the journey of one photographer who took a dive headfirst into an unknown land and found himself deep in the thick of cancer research, postage stamps, and a major metropolitan museum.

From the Dakotas to Dolphins

Before Curaçao and his Nikon D100, there was Rapid City, South Dakota and his film camera. Barry was a nature photographer, mostly postcards and calendars for National Parks. When his wife Aimee got a job offer out of the blue from the Dolphin Academy at the Curaçao Sea Aquarium, there was no doubt. They would sell their new home and cars, pack up their dog, Inca, and move to the Caribbean. In the first few months Barry spent every chance he could get underwater learning to navigate his new Ikelite housing and translating his topside photography skills. Barry’s underwater photography skills developed quickly and soon enough his work was noticed by the staff at the Dolphin Academy where he was hired as the photo shop manager. The next few years were happily spent in the water with the dolphins honing his underwater photography abilities, creating mountain biking trails topside, and enjoying the good life that Curaçao offers.

2014 was the first year Barry's photographs would be used as official postage for Curaçao. © Barry Brown

Substation Curaçao

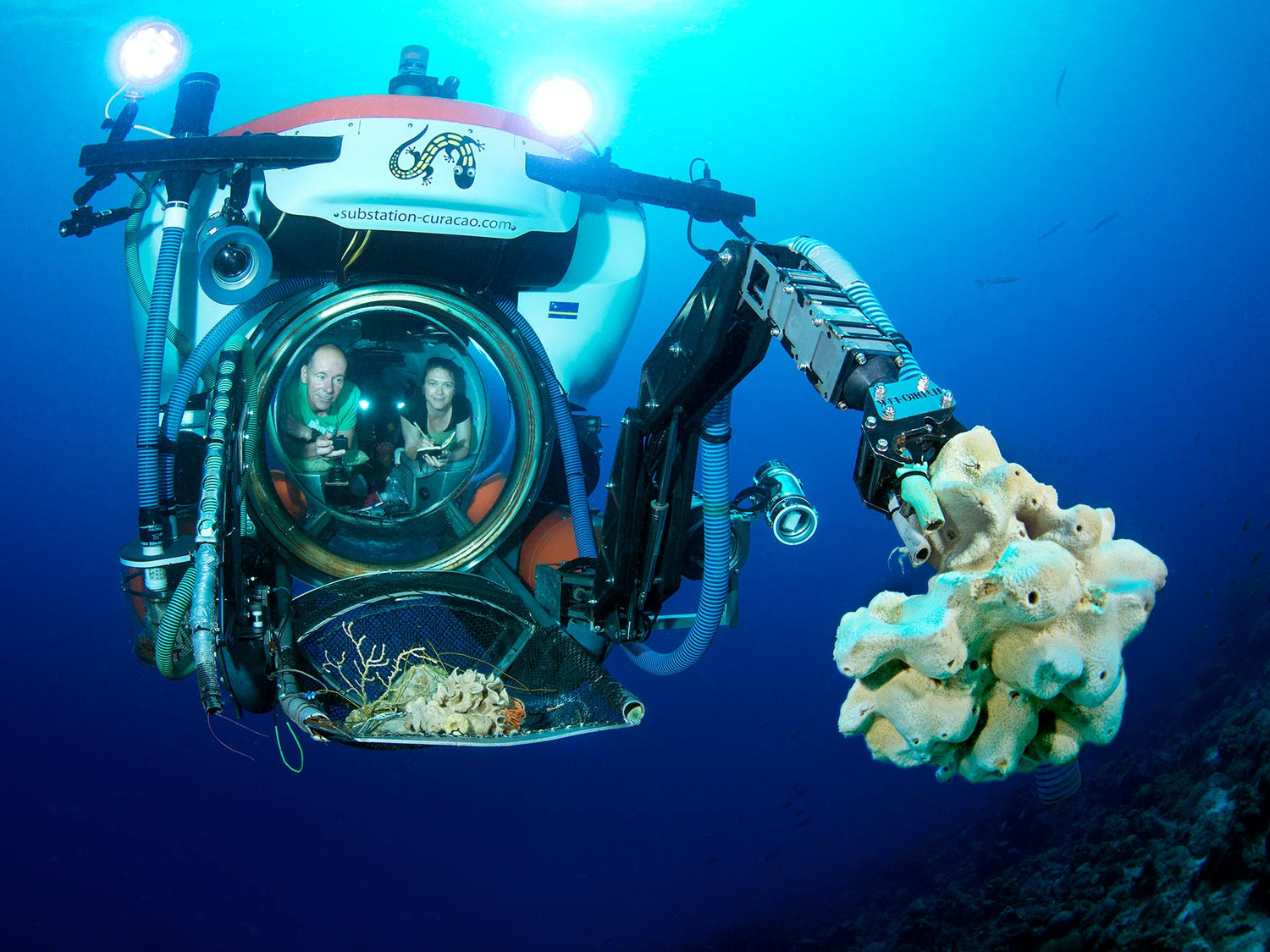

By 2010 Barry left his position with the Dolphin Academy and went to work for Adrian Schrier, known colloquially as “Dutch.” Dutch had recently purchased a $2.5 million submersible and was looking for an underwater photographer to join his Substation Curaçao team. The sub came fully equipped with a robotic arm, vacuum system, collection basket, and a depth potential of 1000 feet (304.8m). Because of the scientific prospects of this vessel, leading marine biologists were interested in finding out how it could aid in their research. Enter Carole Baldwin, an ichthyologist with the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (NMNH), and her team of investigators. Together, with Barry, this team of scientists worked on an assignment known as DROP – Deep Reef Observation Project. DROP’s objective is to study reefs located at depths beyond scuba accessibility, in hopes of examining and monitoring under-explored marine ecosystems.

Carole Baldwin and her team of researchers from the Smithsonian. © Barry Brown

Scorpaenodes barrybrowni

For the next eight years Barry was able to work closely with Carole Baldwin and her team, capturing unprecedented images of never-before-seen deep-sea specimens. They also discovered a handful of new species too. Through tireless research and DNA sequencing, no less than 30 new species were discovered by DROP and Substation Curaçao. One such discovery, a type of scorpionfish, was named after Barry – the Scorpaenodes barrybrowni – a fantastically ornate, 2.5 inch (6.35cm) deep-sea fish. To ensure Barry could photograph the specimens alive, the Curasub team constructed cold, dark tanks to mimic the environment of a 1000-foot (304.8m) seabed. These tanks could hold anything from tiny deep-sea fish to large ones, spiny urchins, or animals that were poisonous. Particularly in the case of poisonous animals it was critical that the Curasub team could house each of these animals separately and safely.

When bringing an animal up to the surface and into the tank proved an impossibility, Barry would meet the submersible anywhere between 50-175 feet (15.24 – 53.34m) and capture the images underwater. Under these circumstances, and being well practiced in the art of a quick descent, Barry would dive in head first and swim toward the sub. Often he was accompanied by a team member who would be tasked with carrying an extra tank to guarantee Barry would have enough time underwater to photograph whatever the researchers needed that day.

Scorpaenodes barrybrowni. This scorpionfish, named after Barry, was one of the 30 newly discovered species by The Smithsonian's DROP team. © Barry Brown

Lunar Landscape

At depths as deep as the Curasub could reach, much of the atmosphere is quite devoid of color. There are no gorgonians or beautiful coral, as these need sunlight to survive. Unlike the neutral backdrop of a 1000-foot (304.8m) ocean floor, the astonishing deep-sea creatures have a complexity of color that amazed both Barry and the researchers. The inanimate objects the team found did not disappoint either. These were often as rare as the undiscovered creatures that swam amongst them. It was not uncommon for the researchers to find bottles and pitchers dating as far as the 1600’s, also not uncommon was to find an octopus hidden within one of these bottles.

Due to the lack of sunlight, much of the seafloor at 1000 feet in colorless, a scene which Barry likens to a lunar landscape. © Barry Brown

Pictured with the Slit Shell is a jug that is hundreds of years old, most likely a product of the Netherlands. © Barry Brown

Living Color

As the researchers collected and sequenced the DNA of the specimens they gathered, Barry got to work photographing his subjects. Be it underwater or in the tank, Barry would spend as much time as possible with any single creature. What he captured was novel. Even among the previously discovered specimen, many of them had never been photographed alive, their living colors as yet unknown to the human eye. These images were integral to the research of the Deep Reef Observation Project. Barry’s photos would go on to become a staple of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and Smithsonian Magazine, framed and hung in the halls of the Smithsonian’s brick-and-mortar building, they would also win awards and countless honorable mentions.

Prior to the innovative work of team Curasub, many fish had never been photographed alive, thus their living colors had never been documented. © Barry Brown

Deep-Sea Snail Mail

The Curasub brought myriad underwater critters and creatures into Barry’s life, and so too did it bring interesting people into his life as well. From the royal family of Holland to Jack Hanna, an untold number of VIPs from Curaçao and beyond would strap in for a ride in the sub and Barry would capture their smiles through the sub’s fishbowl window.

On one of these excursions the Curasub hosted an official of Curaçao's post office, Max van Aalst. This official, in part, helped curate designs for Curaçao's postage stamps. After taking a tour of the facility and seeing the images Barry took for the Smithsonian, he decided they would be perfect for Curaçao's next series of stamps. In the weeks that followed, Barry frequented the post office and, with the help of a graphic designer, the stamps were born. During this process many of the creatures that would be featured on the stamps were as yet unnamed while The Smithsonian investigators continued their research. In time, each creature that made it to a stamp would be named, and Barry’s work would be featured on Curaçao's official postage stamps for the years 2014 and 2019. These stamps would travel around the globe on all manner of correspondance. Today some of these stamps are even sold as collector’s items on eBay.

In 2019 the Curaçao post commissioned another set of stamps from Barry's work. The Flame Scallops pictured here were also a newly discovered species. © Barry Brown

Surprising Sponges

In his capacity as the photographer for the Curasub Barry would eventually go on to work with Sirenas, a biotech company leading research in marine-based therapeutics. Sirenas hired the Curasub team to aid in their “bioprospecting” work, most typically in pursuance of deep-sea sponges. This research aimed to identify possible microbes within the sponges that may have potential benefits in cancer therapeutics research.

In his frequent work with Sirenas, Barry noted the delicacy with which each sponge was treated, packaged, frozen, and shipped back to the United States for research in the lab. Sirenas, like the researchers with Smithsonian’s DROP, were careful to collect only what they needed, never disturbing anything beyond what their research called for.

Deep-sea sponges can be quite toxic and have a wide variety of fragrances. Often after the sponges were brought out of the Curasub’s net, the team’s first notes would be on the scent of each sponge. Some gave off a citrusy, fruity aroma and others smelled like rotting flesh. The surprises within these sponges were bountiful. Upon opening up the sponges, myriad deep-sea fauna could be found, like the six gastropods Barry once discovered and quickly rushed to his cold tank. For such a primitive organism, their smells and hidden surprises prove that a seemingly basic life-form can provide untold treasures, and, with continued research and hope, possibly provide medically therapeutic benefits as well.

The Curasub can reach a depth of 1000 feet (304.8m) within 15 minutes. The possibilities of this submersible attracted guests of all kinds, from scientists to socialites. © Barry Brown

Depths of Experience

Barry can’t even count all the dives he has under his belt, even 5000 may be an under estimation. He also can’t count all of the publications his work is featured in. And that probably summarizes Barry pretty well – he’s not in the market of enumeration, he’s in the market of experience. The experience of living boldly, of saying "yes" when life presents an opportunity, and leaving his stamp on the world.

Barry Brown is an award winning professional photographer, commercial paleontologist, ex-mountain bike racer, and all around Renaissance Man. Today he lives with his wife Aimee in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Aimee, still works with animals as a service dog trainer and Barry continues to produce and publish his photography for organizations like Getty and various magazines. Read more about Barry from his ambassador profile, visit his website, and follow him on Instagram @coralreefphotos.

Denise Pietsch (pronounced “Peach”) currently manages Ikelite’s Photo School and social media presence. Denise hails from New Jersey, where she obtained a degree in Dance Therapy. After years teaching dance she migrated into the corporate world and eventually came around to Ikelite via the natural career path of fruit distribution and early childhood development. In the end, her lifelong love of photography and octopuses combined into the work she does now. In addition to sharing her energy and enthusiasm with the underwater community she also manages social media for her dog, Joe, collects vinyl records, and enjoys creating memories with her friends and family.

Additional Reading

Transformer in the Neutral Buoyancy Lab with the Canon EOS 5DS R

Why You Need Strobes Underwater

Whale Sharks Off Isla Mujeres with Ken & Kimber Kiefer

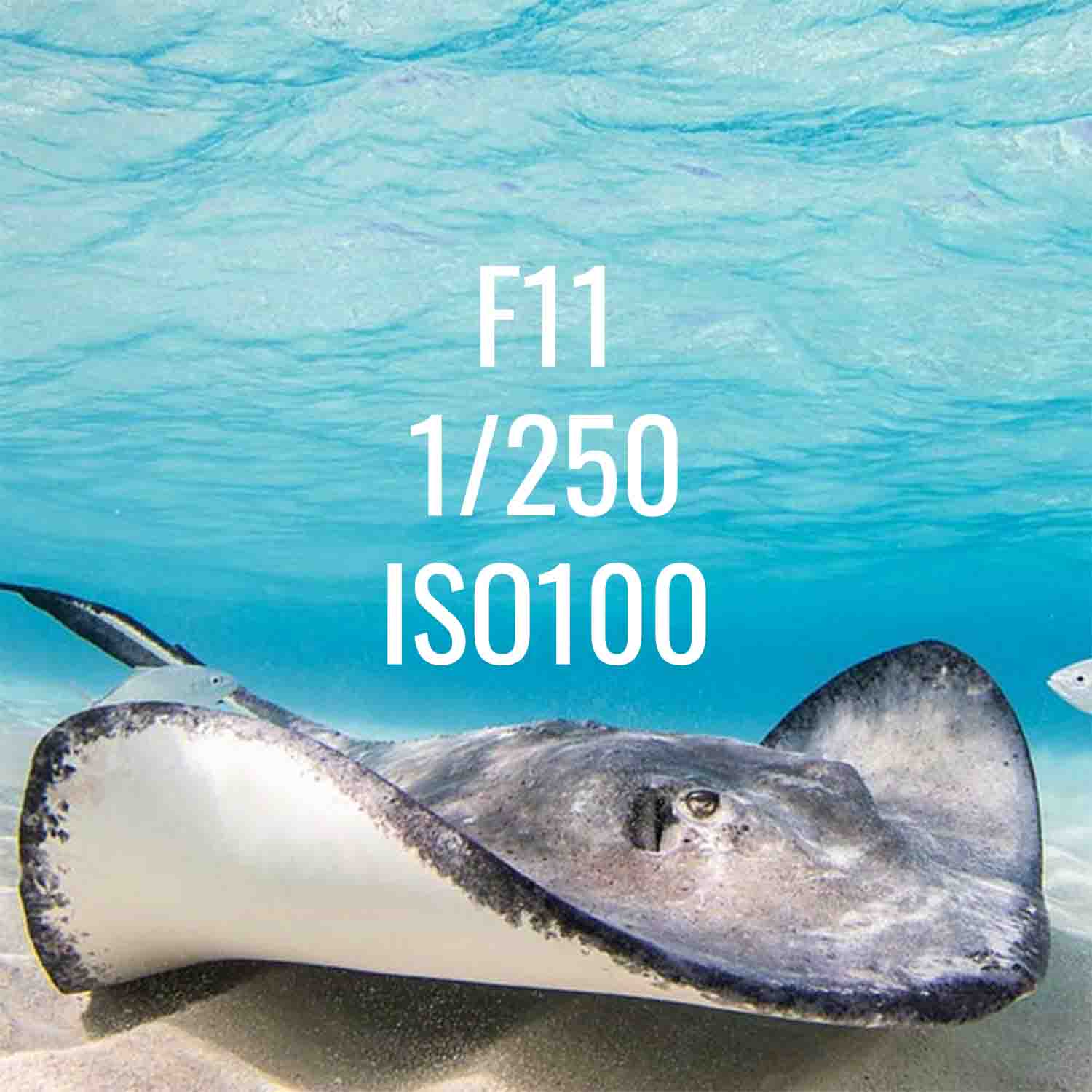

Dolphin Photography Underwater Camera Settings